Norman Bel Geddes

Norman Bel Geddes, born Norman Melancton Geddes in Adrian, Michigan in 1893, became one of the key people who pushed Art Deco design toward the streamlined “machine age” look. He studied briefly at the Cleveland Institute of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, then started working as an advertising draftsman in 1913. After marrying Helen Belle Schneider in 1916, they combined their names and became Bel Geddes. He first built his reputation in theater, designing sets in New York and later working on film projects, including sets for Cecil B. DeMille in the 1920s. In 1927, he shifted into industrial design, encouraged by an auto industry contact, and started producing concept models that imagined what future cars could look like. Even when those early concept cars were not built, the ideas traveled fast through magazines, exhibitions, and clients. By the early 1930s, he was known as a showman designer who could sell the public on the future as much as he could draw it.

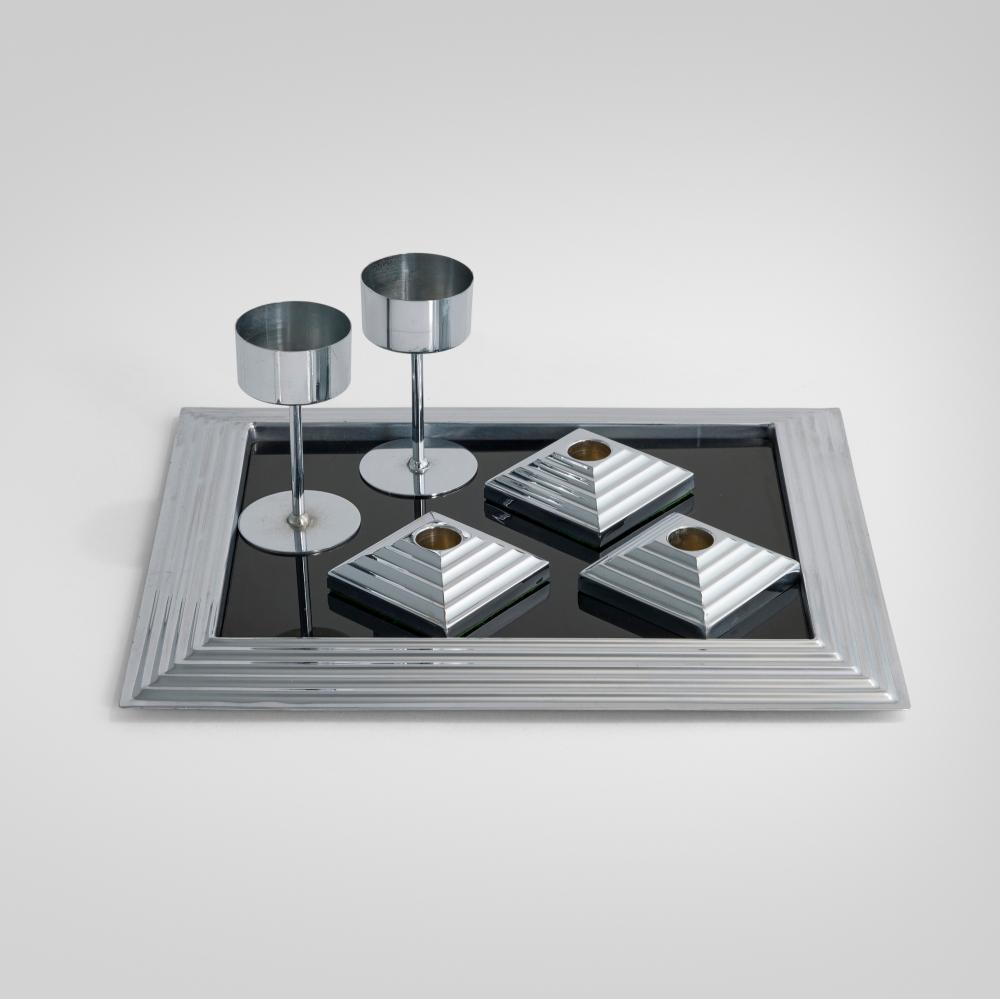

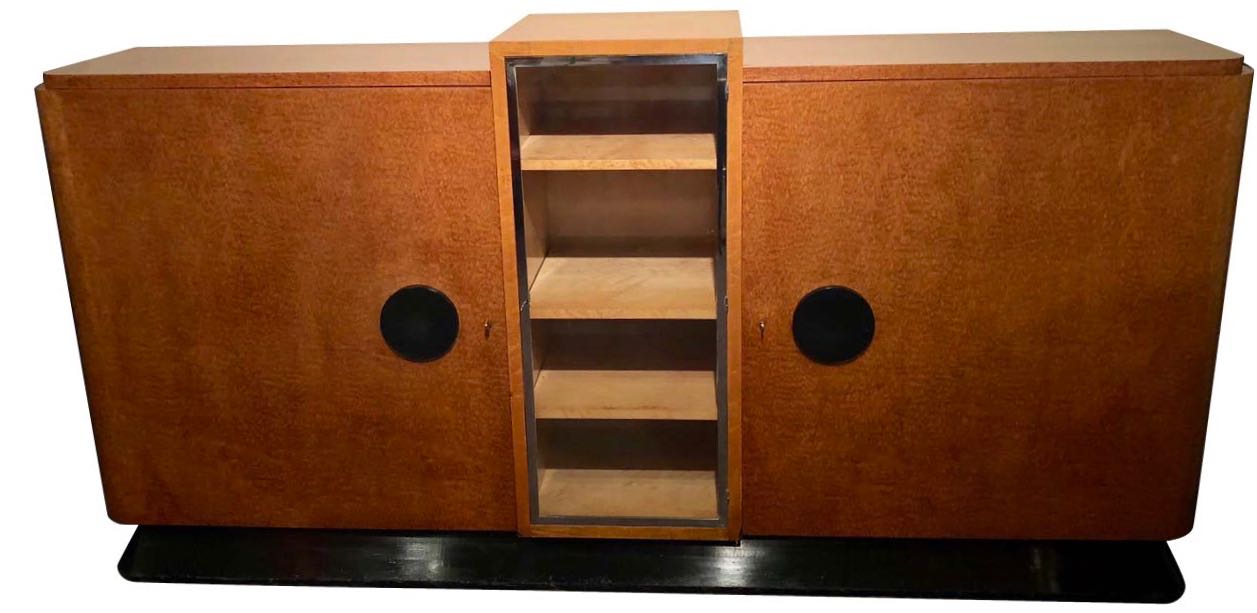

His Art Deco relevance comes through most clearly in how he popularized streamlining as a style, making speed and smooth flow feel like a modern ideal for everything from transportation to home goods. His 1932 book Horizons presented dramatic visions of cars, trains, planes, and consumer products with clean, aerodynamic forms, and it helped make streamlining the signature look of the decade. He designed metal bedroom furniture for Simmons, and his “House of Tomorrow” concept became a widely shared image of modern living. He also worked on real transportation projects, including interiors for Pan Am’s China Clipper aircraft, and his ideas are often linked to the broader shift toward sleek American industrial design in the 1930s. His biggest public moment was Futurama, the General Motors exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where visitors rode through a massive model of a future city built around highways and fast-moving cars. That exhibit shaped how many Americans pictured the future, and it fed directly into his 1940 book Magic Motorways. Later, he helped professionalize the field, including being among the founders of the Society of Industrial Designers, and his influence stayed alive through archives, reprints, and the designers who came after him.

Bel Geddes’s style is bold, smooth, and forward-looking, with forms that feel carved by motion and airflow. He leaned into the Art Deco machine age mood by simplifying shapes into long curves, tapered bodies, and clean surfaces. His drawings often make everyday objects feel like vehicles, even when they are stoves, furniture, or displays. He liked drama and scale, so his work often reads like a vision of a whole world, not just a single product. The result is Art Deco that feels less decorative and more futuristic, built around speed, progress, and modern life.

Key Influences

- Streamlining for the public: Helped turn streamlining into a mainstream design language of the 1930s through images, exhibitions, and products.

- Horizons and mass influence: Used publishing to spread Art Deco future thinking far beyond elite design circles.

- Futurama and the highway future: Made the freeway-based “city of tomorrow” feel normal and exciting to millions of people.

- Transportation imagination: Connected Art Deco style to the romance of planes, trains, ocean liners, and concept cars.

- Industrial design as a profession: Helped establish industrial design as a recognized field through studios, patents, and professional groups.