René Herbst

René Herbst was born in Paris in 1891 and came of age at a moment when traditional decorative arts were being actively questioned. He trained as an architect and designer during a period marked by rapid industrialization and social change. Early in his career, he rejected the decorative excess that defined much French furniture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Herbst was deeply influenced by new ideas about standardization, rational construction, and social responsibility in design. Rather than viewing furniture as a luxury object, he approached it as a functional tool for everyday life. His outlook aligned him with the emerging modernist movement rather than mainstream Art Deco luxury. By the 1920s, he had established himself as a radical voice within French design circles. His work consistently challenged the dominance of ornament and traditional craftsmanship.

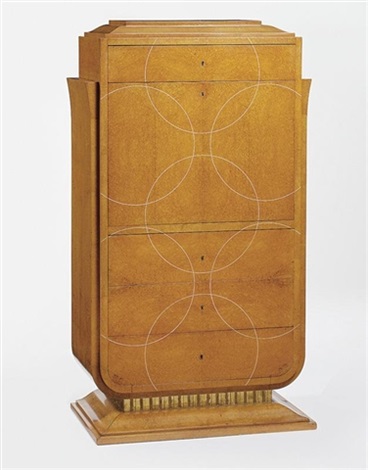

Herbst’s most influential work emerged in furniture design, where he embraced industrial materials such as steel, aluminum, and rubber. He believed these materials offered durability, efficiency, and honesty that traditional woods and veneers could not. His most famous design, the Sandows Chair of 1929, paired a tubular steel frame with elastic rubber webbing originally used in industry. This chair embodied his commitment to comfort, flexibility, and structural clarity. Herbst also designed chaise longues, tables, and lighting that followed the same principles of minimal form and exposed construction. In parallel with his design practice, he played a major role in organizing modernist thought in France. In 1929, he co-founded the Union des Artistes Modernes, a group dedicated to rejecting luxury-oriented design in favor of functional modernism. Through both his objects and his advocacy, Herbst helped define a distinctly French path toward modern design.

René Herbst’s style is rooted in functional modernism and industrial logic. His furniture favors tubular steel, visible structure, and interchangeable components. Ornament is entirely absent, replaced by proportion, balance, and material honesty. Comfort is achieved through engineering rather than upholstery or decoration. His work represents the most utilitarian edge of Art Deco’s transition into modernism.

Key Influences

- Industrial Materials and Engineering: Steel tubing and rubber informed both structure and comfort.

- Social Responsibility in Design: A belief that good furniture should be affordable and widely accessible.

- Modernist Architecture: Functional planning and rational construction shaped his approach to objects.

- Union des Artistes Modernes: Collaboration with like-minded designers reinforced anti-luxury principles.

- Reaction Against Decorative Excess: A deliberate rejection of ornamental French furniture traditions.